The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) recently updated their crime and court data. The information on rape and sexual assault is predictably horrifying.

Details and links are below, but essentially, what the data says is that nine out of ten rape victims are women and children, and nine out of ten rapists are men and boys.

You could fill the MCG twice over with all the women who were sexually assaulted last year and didn’t report it to police.

Maybe we should do that.

My data also shows, as many others have (here, here, here, and here to name a few) that the police and courts are not fit for purpose in responding to sexual violence.

Marginalised people – First Nations women, young women, children, LGBTIQ people, people with disabilities, women living in poverty – are, as they always are, the most at risk of violence and the least able to access even a semblance of justice from police and courts.

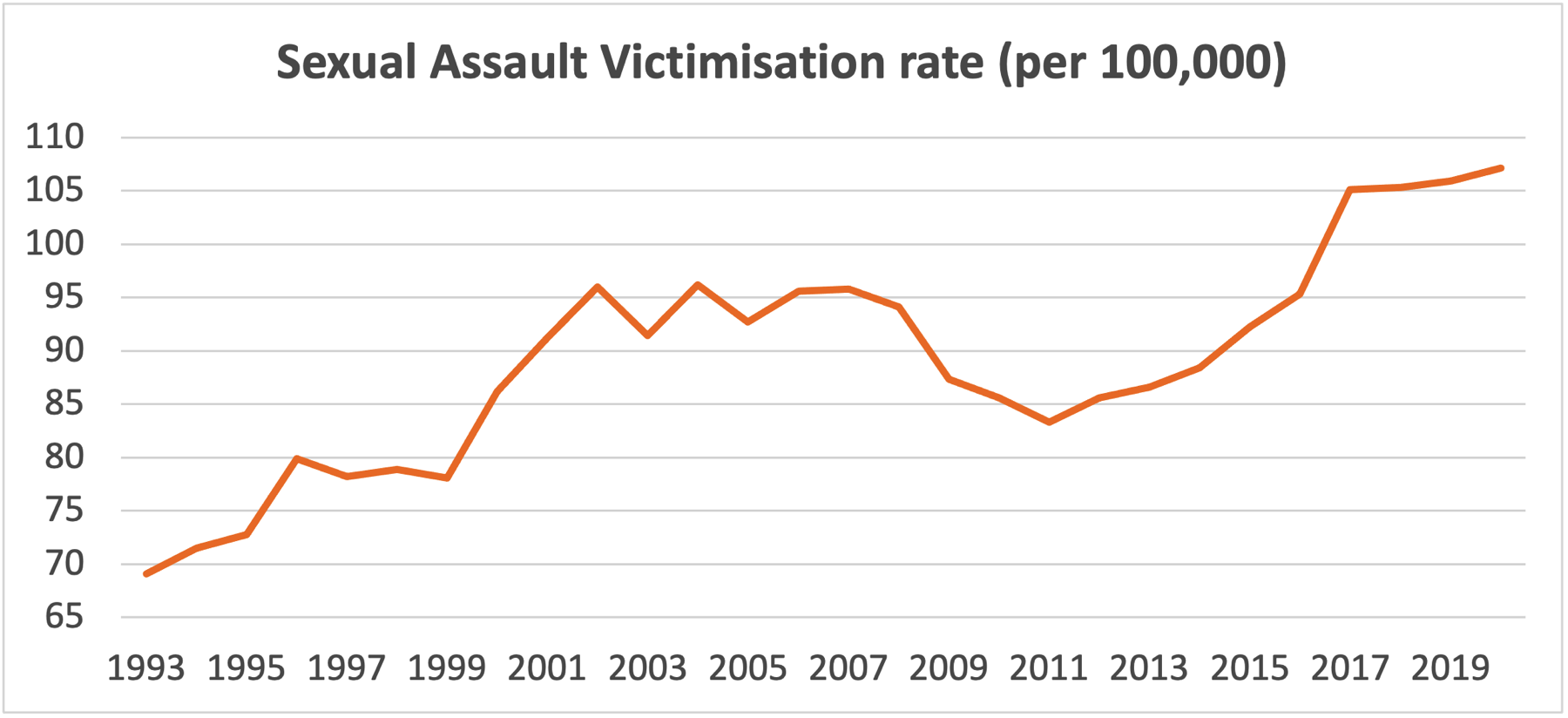

More than thirty years of law reform have not made any change to the number of women and children raped by men and boys. If anything, it appears to be increasing (although it’s difficult to know whether this is an increase in reporting or actual rapes).

Law reform also hasn’t made any difference to conviction rates, or the trauma rape trials inflict on already traumatised victims.

More law reform and better training for police might help a bit, but decades of evidence proves police and courts are too dysfunctional to be fixed by more tinkering around the edges.

We need courageous and empathetic innovation. A system outside police and courts that everyone can access without fear. Something that provides real support for people who have been raped. Somewhere they can have their rape acknowledged without further violation by police, lawyers, judges, or “child protection” bureaucracies. Somewhere that can provide education and rehabilitation to boys and young men, so they don’t become adult rapists. Obviously, it needs to be able to connect to the criminal system when necessary or requested, but it can’t operate within it.

I am by no means the first person to say this. I won’t be the last. But we can’t keep ignoring all the people who keep saying it.

Data and links

- Victims and offenders

- Reported and unreported rape

- Underestimated statistics

- False Allegations

- Courts and prisons

- Change over time

Victims and offenders

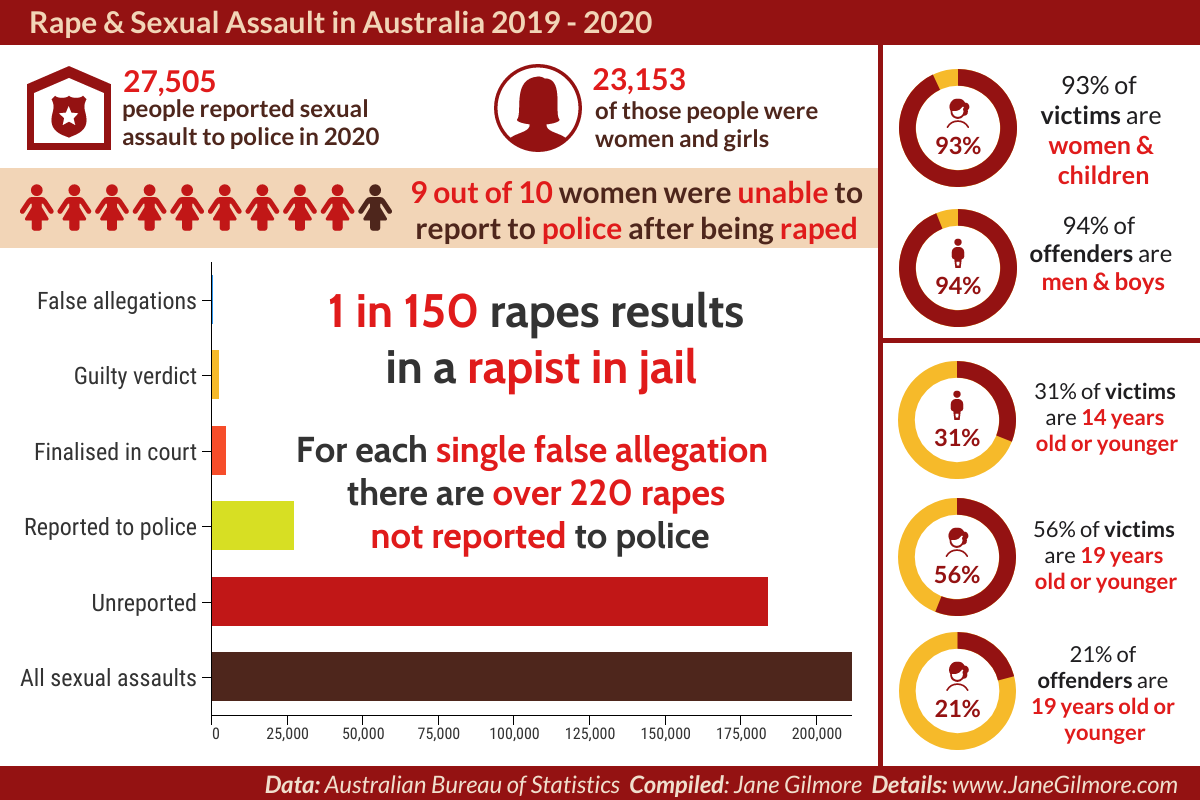

Crime Victimisation data (Table 1) shows 27,505 people reported rape or sexual assault to police in 2020. Of those, 84% were women and girls (Table 2) and 56% were 19 years old or younger at the time. Children and adult women make up 93% of all victims.

Data on offenders shows 8,428 men and 548 women (Table 2) had police proceedings initiated against them for sexual assault and related offences. One in five of them were under 20 years old.

Reported and unreported rape

ABS data estimates only 13% of people who have been sexual assaulted report it to police. A more detailed examination by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare says nine out of ten women who were raped by a man in the last ten years did not report it to police (page 5).

Even using the 13% figure, if there were 27,505 reports, there were 184,072 unreported sexual assaults.

Underestimated statistics

It’s likely the data on reports to police is underestimated. It comes from the ABS Personal Safety Survey(PSS), which is the source of most of our statistics on men’s violence against women.

The PSS assumes everyone contacted is willing and able to spend half an hour telling a stranger the details of their worst traumas.

It excludes very remote areas and anyone who doesn’t live in private dwelling – eg: homeless people, anyone living in care etc.

Additionally, just over 30% of people contacted refused to complete the survey. There’s no way to know why they refused to participate, but it seems reasonable that many of them had good reason to be uncomfortable or afraid of answering questions about physical, emotional, or sexual violence.

Finally, the PSS is what’s called a Conflict Tactics Scale survey, which research shows will often underestimatemen’s violence and overestimate women’s violence.

This is not the ABS’ fault. They can’t (and shouldn’t) force everyone to answer questions about trauma. It’s just a natural limitation of these kind of surveys.

What it does mean though, is we shouldn’t assume the statistics so commonly cited about violence are correct. They are not facts. They are an indication of the minimum level of violence.

So, the most accurate way to report sexual violence data from the PSS is not “one in five women and one in twenty men have experienced sexual violence” because we don’t know that, and it doesn’t include violence that occurred before someone was 15 years old.

At least one in five women and up to one in twenty men have experienced sexual violence since they were 15 years old.

Accuracy matters.

False Allegations

It’s difficult to know for sure exactly how many false allegations of rape are made to police, but all evidence in Australia and other similar jurisdictions indicates the rate is very low. One often cited piece of in-depth research found Victoria Police estimate that about 2% of rape allegations are false. VicPol are not known for their wildly feminist bias, so this seems reliable. Other research suggest it could be 5%. Some go as high as 10%, but this includes police recording “false” allegations because the victim withdrew her complaint or the officer in question deemed her responsible for her own rape.

I used a middle ground rate of 3 percent in my calculations.

Courts and prisons

ABS data on Criminal Courts (Table 1) shows 4,954 sexual assault cases were finalised in 2020-21.

Further breakdowns (Table 10) show 2,571 guilty outcomes for sexual assault and 1,413 sentenced to “custody in a correctional institution”. The rest of the “guilty outcomes” were sentenced to “custody in the community” (3%), fully suspended sentence (8%), community order (17%), fines (4%), other (12%).

Court data doesn’t match exactly against reported crimes because sexual assault cases can take more than a year to get to court. While there are some changes over time, the victimisation rate hasn’t changed significantly in the last two years, so these figures are reasonably indicative of what’s happening between police reports and courts.

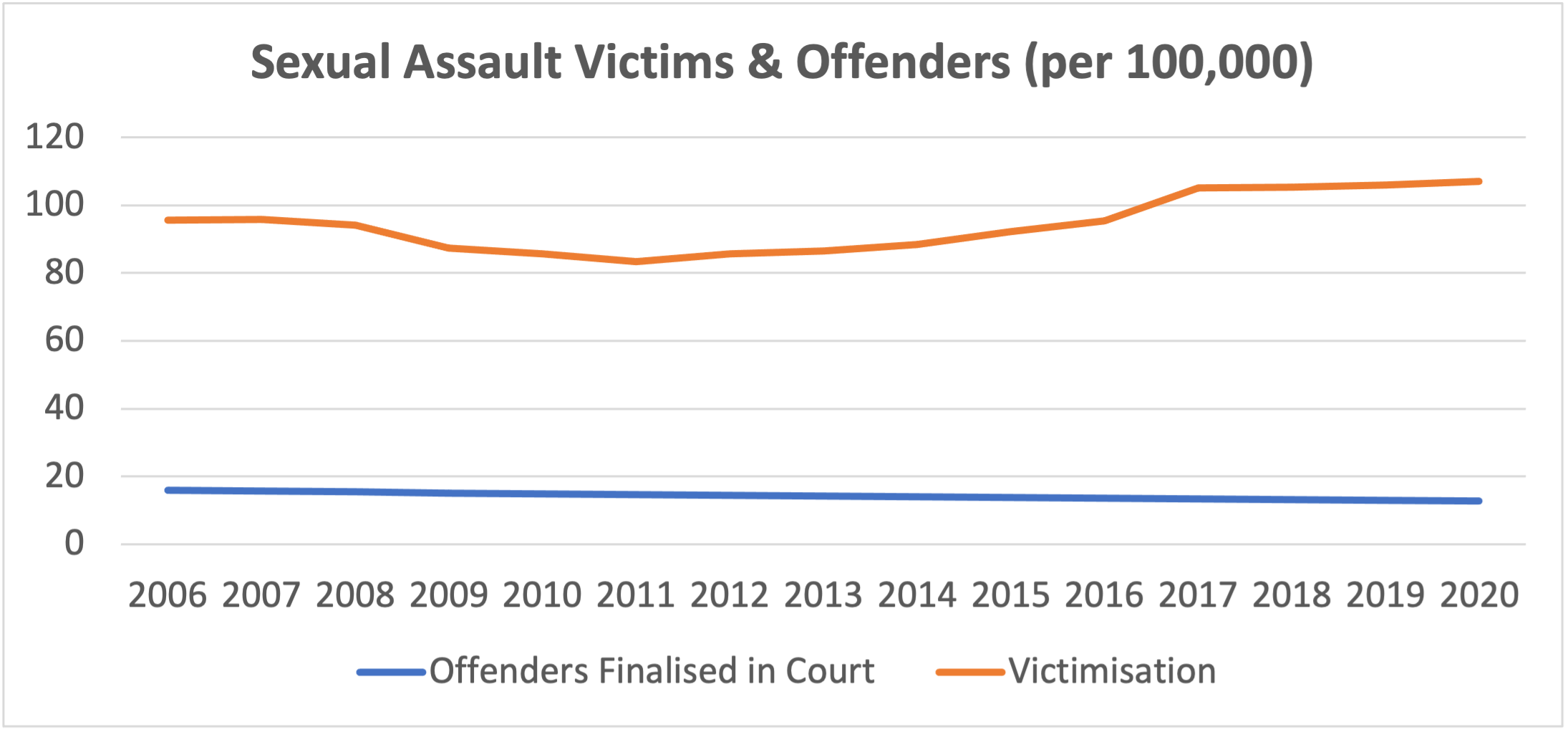

Law reform of sexual assault has been happening in Australia for over 30 years. Looking at data on the number of victims who report to police and the number of offenders who went to court over the last 15 years shows courts have been falling further and further behind.

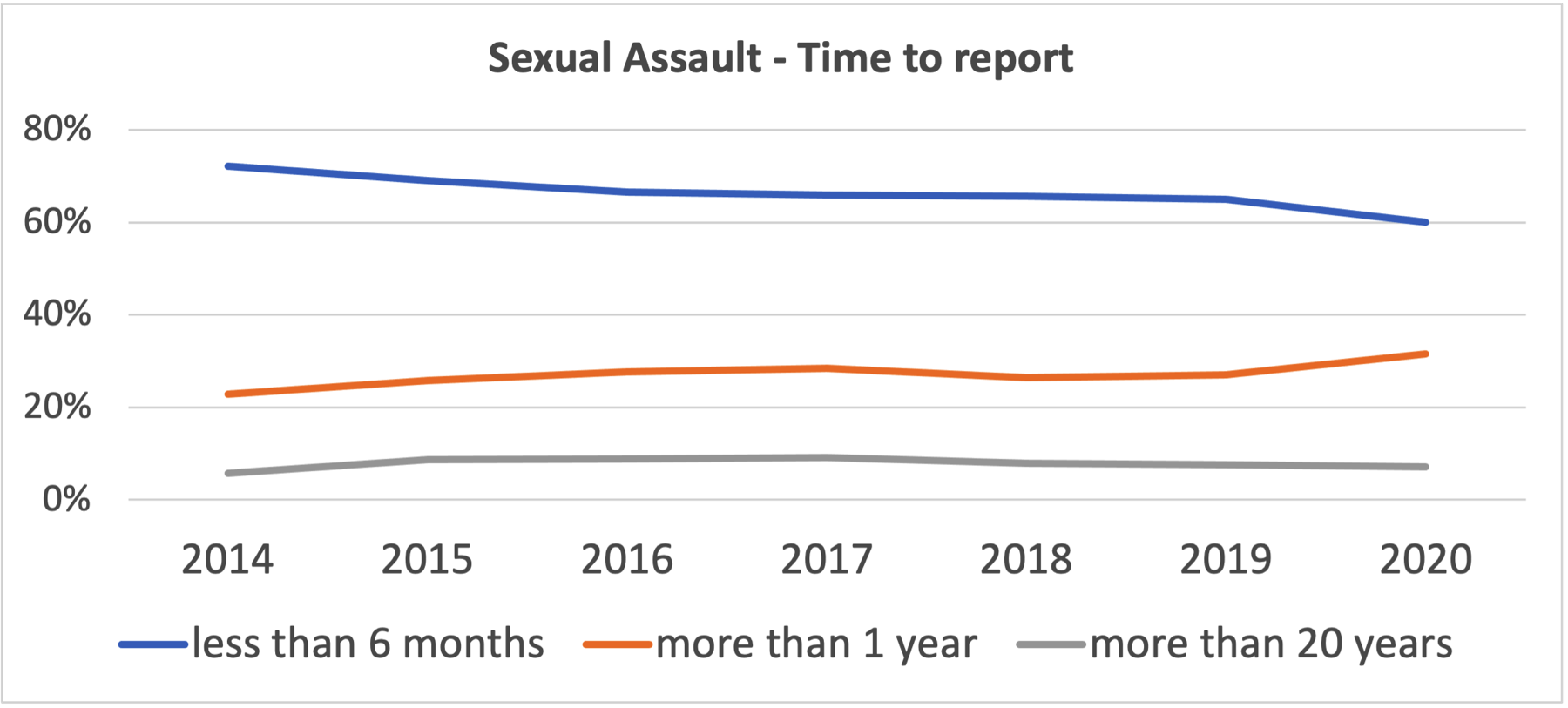

Change over time

The victimisation rate shows how many people per 100,000 of the population reported sexual assault to police in each year. Because we know the vast majority of sexual assaults are not reported, this graph might be telling us that the increase is in reporting, rather than actual rapes. My conversations with police, teachers, frontline services, and crisis workers suggests this is some of the reason for the increase, but not all of it.

The other indication that reporting has increased is looking at the time to report over the last six years. The Royal Commission into Institutional Response to Sexual Abuse of Children had some impact on reporting. We can see this in the increased reporting of sexual violence that occurred more than a year ago and more than 20 years ago. It explains some, but not all, of the total increase.